How Radical Artists Flourished in the Sussex Downs—and Stirred Up the Locals

Sussex Modernism It appears somewhat contradictory—the rolling hills, forests, limestone slopes, and coastlines, favored by vacationers and those escaping London, appear more inclined to nurture feelings of nostalgia and conservatism rather than fostering radicalism and innovation.

This exhibition, inspired by a book with the identical title as stated by curator Hope Wolf, suggests differently.

At the conclusion, you'll be convinced that within Sussex's winding lanes and its distinctive oast houses, vital discussions about living and creating art in contemporary times were taking place just as intensely as those happening in urban centers.

To argue that West and East Sussex served as a breeding ground for modernism necessitates challenging numerous preconceptions—not only those related to Sussex itself, but also regarding the nature of modernism.

The movement is typically understood as predominantly urban, male and belonging to a period roughly spanning the late 19 th up to the middle of the century th century – much like how the world was constantly reshaped by industrialization, urbanization, and conflicts of an unprecedented magnitude.

But from the very first room, the exhibition dispenses with these traditional boundaries, centring its display on a rare copy of Blast , the publication put out by the Vorticists – Britain’s first and perhaps only homegrown radical modernist movement, founded in London in 1914.

It's straightforward to track down numerous enduring notions of modernism as a youthful, masculine, urban movement opposing aesthetics all the way back to the Vorticists, along with some contemporaries, who detested what they saw as overly sentimental "provincialism," which they viewed as the opposite of the ceaseless energy found in cities.

A clamour of opposing perspectives places Christine Binnie’s ceramics – made in the past 10 years or so, and so well after the usual mid-century cut-off point – within sight of Eric Ravilious’s watercolour Interior at Furlongs (1939).

Although quite simple, the artwork would definitely be considered an instance of the kind of saccharine beauty that the Vorticists criticized.

However, Ravilious is actually rebutting such criticisms to embrace the modernist label for himself; he does this by choosing to depict painter Peggy Angus’s snug cottage in a completely different light.

His simple interior design deliberately rejects the weak admiration for beauty.

In 1937, Yorkshire-born Edward Wadsworth, who had been part of the Vorticist movement prior to its brief existence being cut short by the onset of World War I, created a work reminiscent of this approach. Sussex Bypass .

In this scene, the view is hidden behind construction activities, with the jumbled arrangement of wooden poles in front hinting at the area's historic forests.

A resting laborer serves as a testament that both the bustling city and serene countryside are realms of tough, grimy work—not merely the romantic musings of artisans and idle peasants lounging with straws.

An unexpected addition is LS Lowry, famous for depicting the industrial north; however, he is showcased through an oil painting of an ancient windmill in Sussex. Such rarities significantly highlight the exhibition, with another instance being Margaret Benecke’s work. Glacier Forms (1936).

This subtle abstraction represents a form of regional modernism, grounded in the coastal town of Eastbourne. There, Benecke and numerous other female artists and writers resided on Enys Road—a style adopted by an artist who began their work later in life, challenging the common notion that modernism was solely for the younger generation.

A curatorial approach that might be bewildering occasionally shows us things that clearly aren’t modernist, yet this is executed remarkably well at several junctures throughout the exhibit.

The writer Bryher is among several little-known figures who come to light in the show, and her saccharine portrait, painted in 1915 by Luke Fildes, is richly descriptive of the limitations imposed by her gender and privileged background, which she sought to escape when she rejected her birth name of Annie Winifred Ellerman, to take the name of a Scilly Isle.

The portrayal of Bryher vividly illustrates what modernism isn’t, much like the two beautiful historical depictions by Mary Stormont, which are beautifully displayed within pseudo-medieval frames.

A founding member of the Rye Art Club, Stormont’s style was typical of the traditional approach derided by fellow Rye resident Edward Burra, generously represented in this exhibition, notably by Mallows (1955-57), which is notably modernist in its embrace of flowers that could easily be deemed weeds.

However, even as Burra and his fellow modernists undoubtedly looked down upon Stormont and those similar to her, the key point is that although she did not adopt modernism in her artwork, she was far from conventional in her private life. In reality, she reached Rye during the 1890s after running away with her spouse.

Along with Burra’s exceptional artwork, there are various other instances of rebellious floral pieces, such as those by Vanessa Bell who resided in Charleston, close to Lewes, from 1916 up until her passing.

Today, it might be easy to view the comfortably hedonistic Bloomsbury Group as merely moderate revolutionaries, but with Bell’s perspective, this changes. Arum Lilies (c.1919) — undoubtedly a reflection on the losses from the First World War — serves as a reminder that their opinions were highly contentious.

The artwork is positioned across from a scarce display of humor by Duncan Grant, featuring aportrait of Bell’s teenage son Julian depicted as a plump and discontented Roman centurion, which serves asa boldly anti-war message.

Instead of being seen as indulgent, or perhaps even treacherous at the time, the decision to withdraw to rural areas—often associated with the Bloomsbury group—is reconsidered here. It is portrayed not merely as an escape but rather as overtly political, motivated by the necessity for room to reflect, contemplate, and consequently take action.

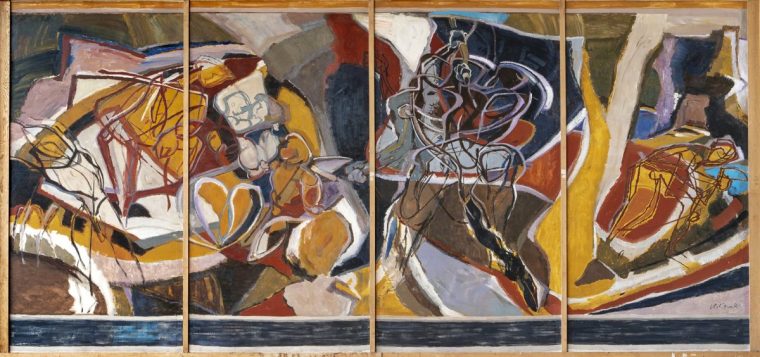

Frequently, the coastline serves as a prerequisite for such complete concentration, much like the nurturing environment within Jean Cooke’s womb-like setting. Cave Painting II (c.1970), the coastline at Birling Gap provides a gateway to an intensely primitive state of being.

There’s something of this, too, in Edith Rimmington’s watery views at Bexhill; the sea a “vast water brain”, echoed somewhat in one of the exhibition’s outstanding moments, a group of seven works made by David Jones during regular stays at Portslade, where the sea seemed to allow him to process his war memories.

The artworks of Jones are exhibited alongside Becky Beasley’s sculptures from 2021, with pieces housed inside vitrines that mirror the tension between confinement and overflow examined by Jones.

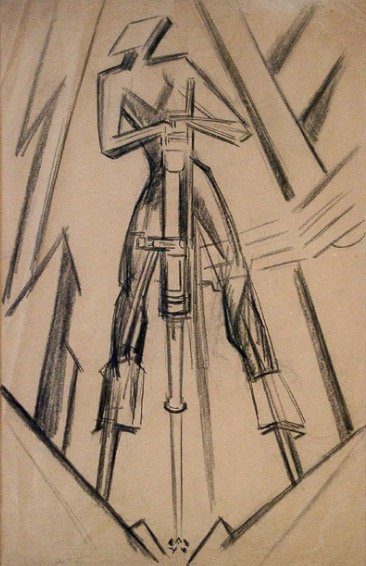

Skeptics may question if extending modernism's lifespan into later periods was merely an attempt to keep outdated ideas alive until new ones emerged. th and even early 21 st the century was merely a distraction to facilitate the incorporation of David Bowie ’s Ashes to Ashes A video from 1980, filmed at Pett Level beach, where its modernist legacy started when sculptor Jacob Epstein established a studio there in 1913 and commenced his work. The Rock Drill.

Actually, the incorporation of works like Larry Achiampong ’s 2020 film Reliquary Created during the lockdown, this work strongly argues against the use of postmodern irony. As various escalating issues like warfare and environmental disasters require a forward-looking, constructive, and essentially positive — modernist — approach to guide us through an increasingly transformative era.

Read Next: Gilbert & George: 'Naturally, we don't own mobile phones—we're not part of the middle class'

The exhibit turns to Jacob Epstein for its most splendidly audacious and transcendent visions of what could be, featuring a grandiose sculpture titled Maternity In 1910, this was created as part of a joint effort with sculptor Eric Gill from Ditchling. The aim was to construct a "twentieth-century Stonehenge" on the Sussex Downs, envisioned as a component of a novel faith influenced by Indian sacred art. As expected, these plans did not come into fruition. It stands alongside patron Edward James’s controversial “surrealistic” plantation of monkey puzzle trees on the Downs—a further instance of how artistic ventures could irk local residents.

This exhibit boasts extensive breadth and depth, spanning multiple decades and mediums, offering a unique insight into the various stances and viewpoints that have coexisted, sometimes uneasily. Following World War II, dissatisfaction with national administrations that led Britain into conflict twice fueled "regionalism." Notably, Eastbourne-based artist Harold Mockford identified as a regionalist.

William Gear, who led the Towner Gallery from 1958 to 1964 as its director, faced strong opposition when he attempted to introduce abstract art to the institution and abandon its "Sussex-themed Works" focus. His endeavors sparked controversy so intense that even the Vorticist movement members would have found it impressive.

By 28 September, Towner Eastbourne townereastbourne.org.uk )

Post a Comment for "How Radical Artists Flourished in the Sussex Downs—and Stirred Up the Locals"