Ancient Underwater City: Revealed After 140,000 Years in Malaysian Waters

- EXPLORE FURTHER: Buried metropolis found within extensive sand dunes

Lying underneath the ocean near the coastline Indonesia Scientists have achieved an earth-shattering breakthrough that might redefine the narrative of our early beginnings.

The cranium of Homo erectus, an ancient human ancestor was found more than 140,000 years after it was initially buried, encapsulated under layers of sediment and sand in the waters of the Madura Strait situated between Java and Madura islands.

Specialists believe the location might provide the initial tangible proof of the vanished continent, an ancient land mass called Sundaland which once linked parts of Southeast Asia. Asia on an extensive equatorial flatland.

Alongside the skull bones , researchers retrieved 6,000 fossil specimens belonging to 36 different species, which included remains of Komodo dragons, buffaloes, deer, and elephants.

Several of these specimens showed intentional cut marks, indicating that early humans employed sophisticated hunting techniques.

These discoveries offer a unique look into the lives of ancient humans and the vanished landscapes of Sundaland, shedding light on how early human communities behaved and adapted to shifts in their environment.

The fossils were found by marine sand workers in 2011, yet specialists only recently determined their age and classification, signifying a significant achievement in the field of paleoanthropology.

'This era was marked by significant variation in physical structure and movement among human ancestral groups within this area,' stated Harold Berghuis, an archaeologist from the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, who headed the research effort.

Between 14,000 and 7,000 years ago, melting glaciers caused sea levels to rise more than 120 meters, submerging the low-lying plains of Sundaland.

The discovery began during marine sand mining in the Madura Strait, where dredging brought up fossilized remains.

Near a land-reclamation area close to Surabaya, employees discovered more than 6,000 vertebrate fossils together with two pieces of human skulls.

Acknowledging their significance, researchers initiated comprehensive surveys, meticulously gathering and classifying the discoveries for examination.

To comprehend the finding, scientists examined the strata of sediments where the fossils were discovered and revealed an ancient buried valley system originating from the former Solo River, which previously coursed eastwards over what is now the submerged Sunda Shelf region.

The sediments in the valley suggest a vibrant river ecosystem existed during the late Middle Pleistocene period.

Homo erectus represented a significant milestone in human evolution. These beings were the earliest ancestors to bear a closer resemblance to modern humans, featuring tall, robust frames, elongated limbs, and shortened arms.

Determining the age of the deposits was essential. Scientists employed Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) techniques on quartz particles to establish the time since these materials were last illuminated by sunlight.

This positioned the valley fill and fossils between approximately 162,000 and 119,000 years ago, clearly during the late Middle Pleistocene epoch.

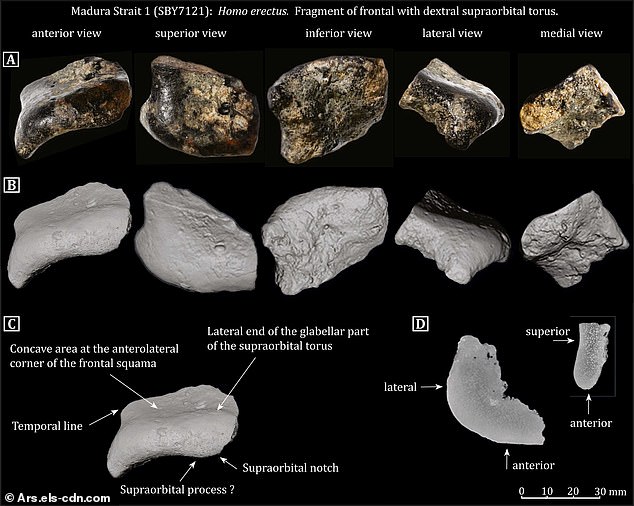

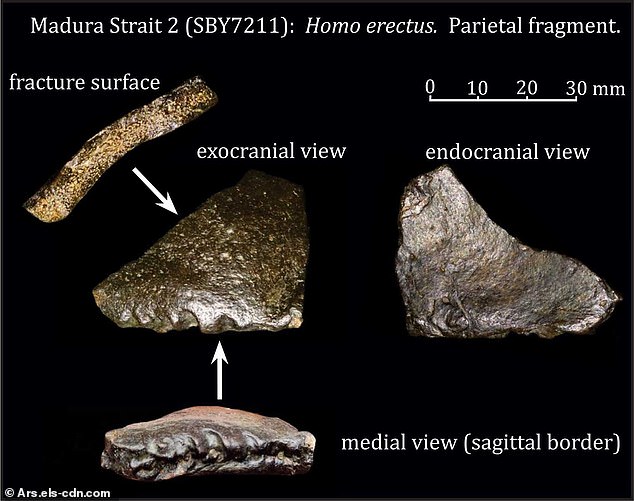

The two Homo erectus skull pieces, consisting of a frontal and a parietal bone, were examined alongside known Homo erectus remains found at Java’s Sambungmacan location.

The closely contested match verified that the fossils found in the Madura Strait belong to Homo erectus, thereby extending this species' recognized habitat into what is currently the submerged Sundaland area.

This site is now recognized as the first location of underwater hominin fossils in Sundaland.

The team also found fossils of an extinct genus of large herbivorous mammals similar to modern elephants, known as Stegodon.

This creature could reach up to 13 feet at the shoulder and weigh more than 10 tons.

Their molars had more ridges than early elephants but fewer than modern elephants, indicating an intermediate evolutionary stage.

Various types of deer remains were also uncovered, including bones and teeth from several species, indicating a diverse and healthy deer population.

The presence of deer is significant because they are key indicators of the environment that once existed, typically open woodlands or grasslands with sufficient water and vegetation to support grazing and browsing animals.

These deer would have been an important food source for predators, including early humans.

Fossil remains of antelope-like creatures add more evidence to the idea of ancient grasslands as their habitat.

These creatures usually favor expansive areas over thick woodlands; hence, their fossils assist in portraying an old terrain resembling prairies or savanna-esque regions.

This research provides the initial concrete evidence of early humans' existence in the submerged regions of Sundaland, thereby questioning previous assumptions regarding the geographical boundaries of Homo erectus.

This underscores the crucial part that submerged landscapes have in mapping out human evolution and movement throughout Southeast Asia.

Berghuis and his team show how integrating techniques from geology, archaeology, and environmental studies can uncover forgotten parts of our past buried under the ocean.

Between 14,000 and 7,000 years ago, as glaciers melted, global sea levels rose by more than 120 meters, inundating the lower areas of Sundaland. This displacement compelled many settlements to move inland or to elevated islands.

The fossil finds from the Madura Strait form only one part of an intricate jigsaw stretching across different continents and ages. With the progression of subaqueous exploration technologies, researchers aspire to reveal the submerged urban centers, agricultural fields, and forgotten histories concealed beneath the waters.

Read more

Post a Comment for "Ancient Underwater City: Revealed After 140,000 Years in Malaysian Waters"