Beware the Dragons of Taiping: A Cautionary Tale

TAIPING: They say that sailors and cartographers from medieval times labelled uncharted regions of the globe with the phrase "Here Be Dragons".

It was likely meant as a message to ship captains not to be reckless when sailing through unfamiliar waters in search of riches in undiscovered territories.

Of course, dragons do not actually exist in our world. However, just like millennia ago, these mythical creatures continue to thrive in folklore and myths, even within religious narratives.

A lot of Malaysians link dragons to Western culture as well as Chinese traditions, largely due to the frequent dragon dance presentations by the Chinese during festivities and significant occasions.

While lesser-known, dragons and serpents play or have played a significant role in the majority of Southeast Asian cultures, including Malay traditions. Additionally, the "naga" serves as a common cultural element throughout Malaysia and the broader Southeast Asian region.

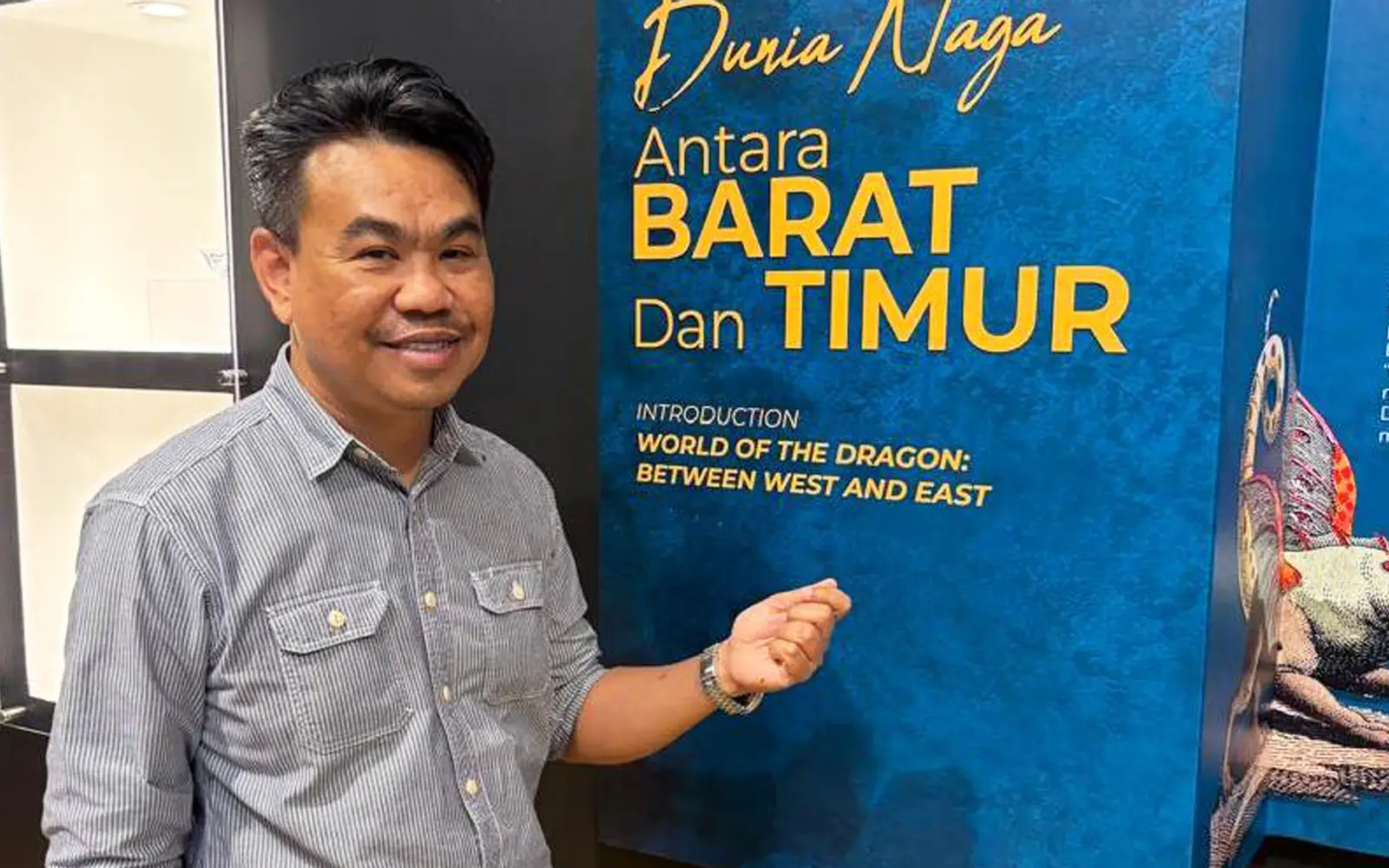

This is what a new exhibition at the nation’s oldest museum – the Perak Museum in Taiping – explores. The exhibition, which began early this month, will end in January 2026. All exhibits belong to the Museum Department.

Perak Museum director Nasrulamiazam Nasir said dragon motifs and decorations began with carvings on reliefs and sculptures in ancient temples and later became a feature of cultural items: the keris, wayang kulit, puppets, jewellery, textiles, ceramics and royal regalia.

He mentioned that there is a significant distinction between Western and Eastern dragons. "In the West, dragons are viewed as dark, terrifying, and malevolent creatures; they possess wings allowing them to soar through the skies and breathe flames capable of incinerating both beings and objects, often linking them to wicked leaders."

But in the East, dragons are regarded as symbols of goodness, prosperity, strength, and nobility. The viewpoint differs.

He mentioned that the naga or dragon was linked to elements of the natural terrain like rivers, lakes, springs, waterfalls, and mountains.

In Southeast Asian cultures, the dragon was often depicted as being more serpent-like rather than resembling traditional dragons, and they referred to it as "sarpa," which means snake in Sanskrit. In Old Jawi, similar to its usage in the Malay language, it was termed “naga.”

Although the notion of serpent spirits was present within certain communities across Southeast Asia prior to the emergence of significant religious practices in the area, experts suggest that these societies embraced the concept of naga veneration from Indian traditions since much of the land had been influenced by India during various periods.

However, it is uncertain how the naga of India and the dragon of China became conflated.

Nasrulamiazam said: “At one time, nagas were a part of Malay art and culture too. However, when Malays adopted Islam, which prohibits decorations resembling humans and animals, these fell out of favour.

However, prior to that, nagas were featured on various cultural items like pottery and gongs. These creatures also appeared in wooden sculptures crafted by Malays, particularly adorning the prow of a boat (perahu), the handle of a weapon, and bird snares (jebak puyuh).

The displays we have show how the naga motif is used in functional artworks across Malaysia and nearby areas like the kris, fabrics, metal crafts, gongs, and ceramics.

Nasrulamiazam mentioned that dragons had strong ties to the political authority of monarchs in Southeast Asian nations. He noted that in certain countries like Laos and Cambodia, these creatures were regarded as guardians of their rulers.

Monarchs frequently linked themselves to dragons, sometimes asserting they were descendants of dragon princesses. Numerous tales tell of influential leaders who wedded dragon princesses and established thriving realms.

Nasrulamiazamsaid observed that the naga imagery was embraced not only by Malaysia's Orang Asli and Dayak communities but also became an integral part of the Malay rulers' royal regalia throughout history. He further mentioned that this motif persists today as adornment on the keris—a emblem of authority—used during official ceremonies in both Malaysia and Indonesia.

Nasrulamiazam mentioned that the museum aimed to foster a sense of solidarity among Malaysians with this exhibit.

"We possess various cultures and belief systems, and this exhibit demonstrates how these distinct cultures impacted one another, coexisted harmoniously, embraced novel concepts, and incorporated those changes," he stated.

The museum has scheduled various events up till January next year, featuring drawing and meme-making competitions along with quizzes, a scavenger hunt, and lectures.

Nasrulamiazam hopes that the allure of dragons can entice students back to the museums.

On May 18, World Museum Day, adult visitors will not be required to pay the usual RM2 entrance fee.

Taiping, it seems, can certainly claim: Here be dragons.

Post a Comment for "Beware the Dragons of Taiping: A Cautionary Tale"